Although light is the photographer’s primary element, Balarama Heller likes to shoot in the darkness of night. “It signals to the viewer that you’re in an alternate and extraordinary space,” he explains. Heller’s new series, Earth Mass, documents that space: between the spiritual and natural, instinct and science, intimacy and scale. For the first installment of Witness, our new editorial series in partnership with Leica Camera, NeueJournal sat down with Heller to talk process, spontaneity, his Hare Krishna upbringing, and his very first Leica Camera.

NEUEJOURNAL

Let’s start with the title, Earth Mass. Where did that come from?

BALARAMA HELLER

The title refers to the creation of a kind of church, or temple, or shrine in the open air, and references the sense of reverence and worship that I’m trying to bring into nature. It’s obviously secular, and not connected to a specific religion, but it does reference this early Hindu and Greek notion of an Earth goddess — called Gaia, or Devi — this original deity of creation, who wasn’t necessarily a nurturing one — she was also a brutal god.

In this project, I’m circling back to these archaic forms of reverence that exist in human culture. So that’s where I came up with the title Earth Mass. I know “mass” references Catholicism, but I feel that’s also a universal term.

NEUEJOURNAL

That’s so interesting because I was thinking that it had to do with the physical mass of the Earth.

HELLER

Totally. I use that word because I understand it has two references. To your point, I want to bring science into my work and how science is an access point to spirituality. There’s this full circle going on where we’re taking on these archaic forms of worship, but filtering them through science and still kind of coming out with the same sense of divinity.

NJ

One thinks of the spiritual as something you can’t photograph. What is the relationship between photography and spirituality for you?

BH

To answer very directly, in a way photography is the medium of spirituality because it’s dealing with the most intangible element in the universe, the most transitory, the most elemental, which is light. And light is often archetypically seen as the metaphor for all things spiritual. It’s transient, yet it’s all-pervasive. So in a sense photography is the perfect tool for exploring spirituality because its primary medium is light.

NH

Let’s talk about light. All of these photos are shot in darkness — at nighttime. I’m curious if you knew that going in.

HELLER

Yes. I’ve been making images at night, in nocturnal environments, for the past 11 years. Night, to me, is like this theater of mystery: it signals to the viewer that you’re in an alternate and extraordinary space. The senses become heightened due to the inherent unknowns — you’re almost like a predatory cat, prowling and alert. Night is also a space where dreams happen, and a space where we learn to trust our visions and instincts. Conceptually, it makes a perfect setting for my ideas. On a visual level, by working in complete darkness I can control the light more. Because everything is dark, it’s only the light that I add that ends up on the negative.

NH

How did you conceptualize the project? What were the confines you had at the start?

HELLER

I knew I wanted the project to be at night, [with] this reverence involving nature and animals. I’d been revisiting this project I did in the Everglades [Zero at the Bone], and I wanted to make an extension of that. I didn’t feel like it had been quite wrapped up, and I wanted to see if I could continue it in a different environment, the Northeast forest.

My process always begins with a lot of pre-visualization and drawing. Drawings that I will not share with anyone except my girlfriend because they are basically stick sketches. I work with a lot of reference images. I sequence them in a sketchbook, and then go out into the field and try to create them. And then after I’ve created about ten [images], I organize them, I look at them, and then I make more drawings, seeing what needs to be further created, what needs to be cut. Then I’ll go back in the field and I’ll probably cycle through that process five to six times before something very cohesive comes together.

It’s this mixture of having a pretty clear plan and vision for the project and leaving room for spontaneity and accidents. It’s usually in that spontaneity where the best images and the magic happen.

NJ

Which of these images would you put in the “happy accident” category?

HELLER

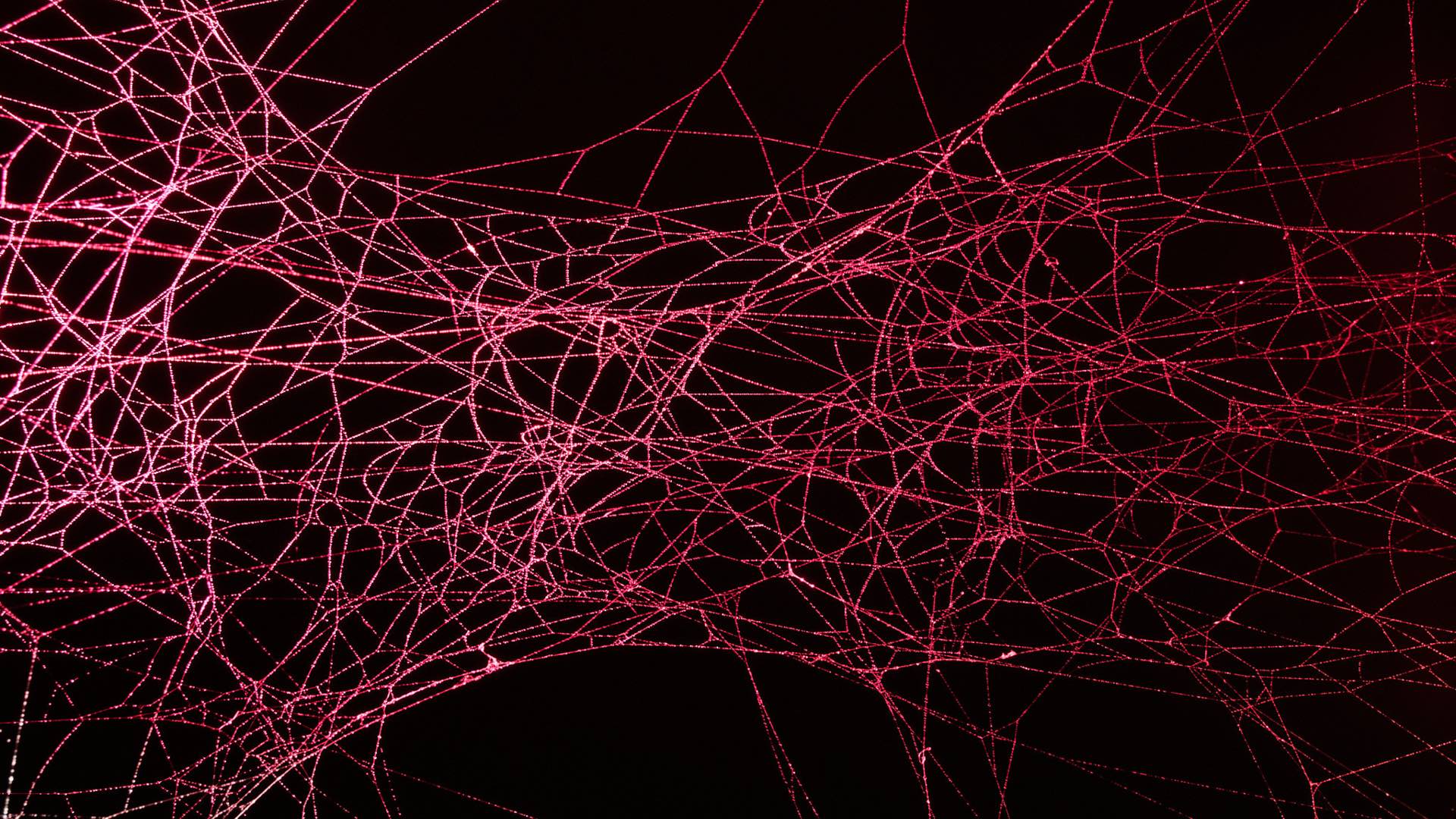

I would say the one where it almost looks like a star space, but with trees. It’s red and there are trees illuminated, it’s looking up into some barren pine trees. [When photographing] this one there was the surprise element of rain, which is nothing I could have planned for, and that I even had trepidation about going out shooting.

But I figured out a way with umbrellas and plastic bags and timing, to use the moisture and rain and figure out where to place myself under these trees to create this really atmospheric, full, stellar environment.

And then there are smaller things, like the final image of the apple. I could have never planned for this mosquito to be so perfectly placed and ominous-looking on the twig. It just came together and looked perfect. It seemed so much more activated, as an image and as a narrative, than if that mosquito hadn’t been there.

NH

What is the story of these animals? The way they’re shot suggests that maybe they’re not just being encountered in the wild. It seems like there is something more going on.

HELLER

My images are supposed to live in a universe separate from reality — so sometimes, telling people how they’re made ruins the illusion a little bit. They’re supposed to exist outside of linear time and outside of contemporary spaces. But there was a lot of production that went into arranging these animals because obviously, I didn’t find them in the wild. I worked with the Southern Vermont Natural History Museum, which operates a rescue facility for wildlife that’s been damaged in one way or another and has no chance of being rehabilitated and reintroduced into the wild. I have a relationship with them, and they allowed me to work with some of their animals, including the two barred owls, which were blind.

NH

Before we move on to talking about your relationship with nature, you mentioned that in the pre-production phase you’re working with pre-visualization and then also references. What are some of those visual references?

HELLER

They’re almost archetypes: images that I find in texts about mythology from different cultures, including the Hare Krishnas — the culture I grew up in — to Greek mythology, to religions from pre-Columbian Mexico.

NH

What is the Hare Krishna relationship to nature, if you can characterize it?

HELLER

Growing up in the Hare Krishnas gave me — well, one could say indoctrinated me with — a very specific, cosmological worldview that is pretty opposite of the standard American one. [My] main connection to the Hare Krishna worldview is this sense of divinity that permeates everything in the universe. That everything is animate, alive, has narrative and meaning. Because of that perspective, I never felt alone when I would spend time in solitude in nature. You feel like you are surrounded by all these beings and, at the very least, by a life force as an accompanying friend in this non-threatening way. I always felt very comfortable in the wilderness as a result of that.

“The camera design is so simple that it gets out of the way of the artist. It reduces the space between you and what you’re trying to achieve. It’s doing what I believe all technology should do.”

NH

You mentioned you’d had a chance a while back to shoot with a Leica and loved it. What were you looking to take advantage of in terms of having this special piece of equipment?

HELLER

I got into photography pretty young, in my teens, and my heroes were people like Josef Koudelka, this lyrical, documentary tradition. It wasn’t about the subject they were photographing, it was about this poetry they were creating with the camera. And it turned out that their cameras were Leica Cameras. I worshipped these artists and made it an early goal to get one — I worked at gas stations and odd jobs on farms or wherever I could — to save up enough money for a Leica Camera M3 from like, 1954, and a lens. It became like a relic to me: this spiritually imbued, powerful object that would allow me access to intimate situations, and offer me a cloak of invisibility, and gave me this kind of superpower.

So to come full circle, the way the tool worked for me when I first started using a Leica Camera in the late 1990s, is the same: the camera design is so simple that it gets out of the way of the artist. It reduces the space between you and what you’re trying to achieve. It’s doing what I believe all technology should do, which is to disappear and become invisible.

In that sense, when I’m working with these delicate subject matters and trying to access these subtle realms of spirituality, the Leica Camera [SL2] is a very useful tool because it doesn’t inhibit me with complications. It is just this fluid process where I can move right into the space I need to.

NH

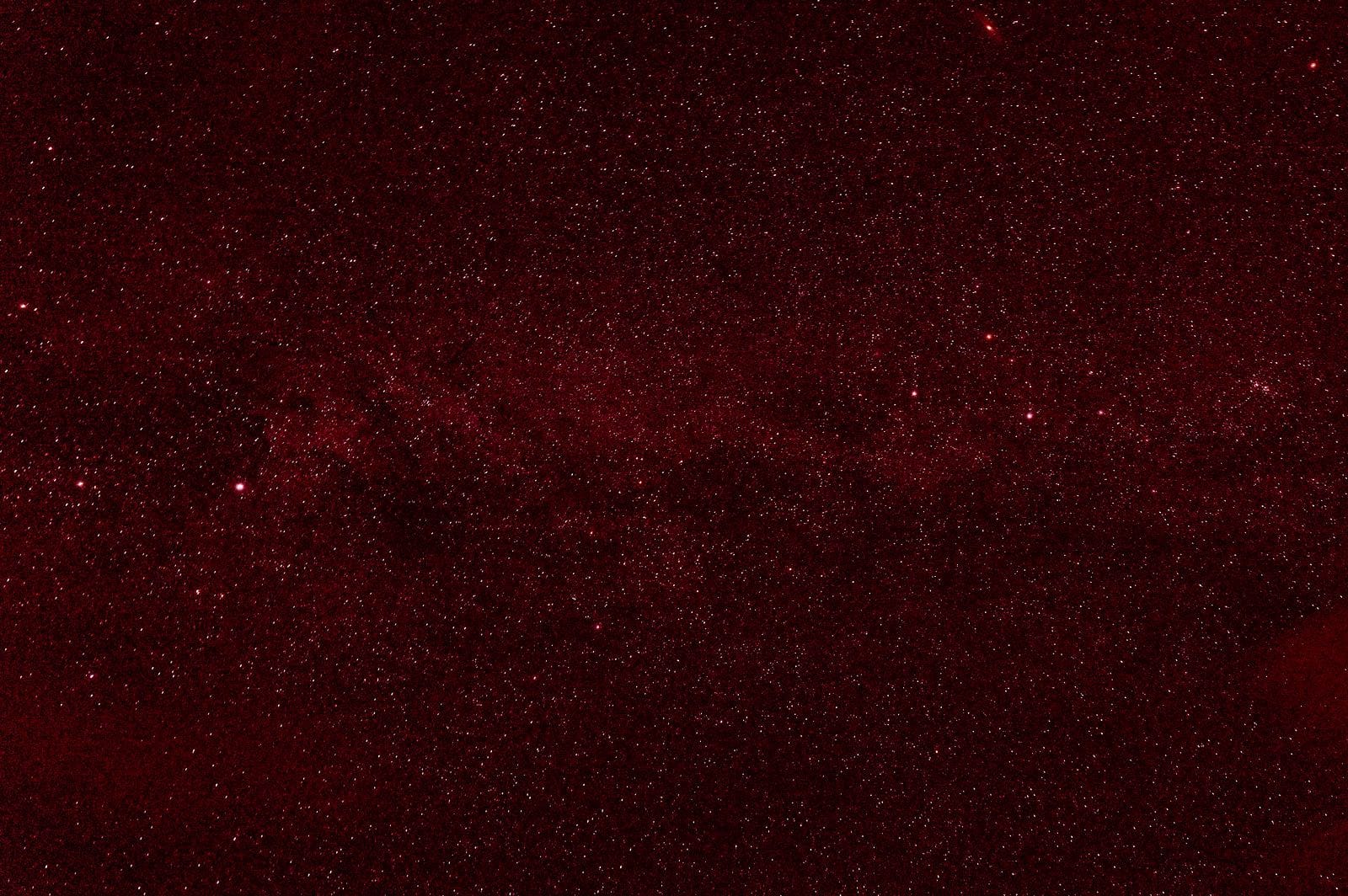

Let’s talk about some of the specific images. I have to ask about this image of the stars.

HELLER

I had never really made an image that was just like a successful Milky Way star field, so I wanted to do that for this project in order to give the viewer a sense of scale and of smallness at the same time. A sense of losing perspective, which sometimes can happen when you’re just lost in a very, very starry night. But also shifting [that perspective] a little bit: most people are not going to see a red-hued Milky Way with their naked eye.

In most of my work, using this red color signals to the viewer that they are in an extraordinary space. You’re not in your waking life space, necessarily. That was the point of making this image. It turned out much better than I’d hoped. A lot of the redness often reads as something biological. [These sky images] could be, perhaps, scientific images of the body or biology. And they sort of live between those spaces. As Carl Sagan says, we’re made of star stuff. So there you go.