Renowned architect Tom Kundig (FAIA, RIBA) and celebrated writer Mark Rozzo connect for a conversation on how residential design continues to evolve in response to the pandemic, and the increasingly complex demands of our home environments.

Shared specially with NeueHouse, the conversation touches on many of the design principles that have run throughout Kundig’s career, particularly the importance of designing for the human experience and prioritizing adaptive reuse—ideas that have shaped Kundig’s residential and non-residential work around the world and are exquisitely captured in the recently released monograph, Tom Kundig: Working Title.

Mark Rozzo: Everyone’s thinking a lot more these days about shelter and space – what their surroundings are and where they are in the world, and why they’re making those choices. As we’re all spending more time our homes, we’re thinking about that specific space a bit deeper. How is that playing out for you, Tom?

Tom Kundig: Instead of traveling so much, right now I’m able to sort of reengage with my home, which has been interesting. I don’t think I realized how much I enjoy being here. If I’m working through something, I can move to a different spot or even go sit in the garden. I’ve been able to totally experience the changing weather as Seattle transitioned from winter to spring to summer, and now into fall. I try to think of it as an opportunity rather than a restriction, and that’s helped make the adjustment easier.

MR: You’ve said that something that guides your practice as a designer of houses is that a house should feel like a human being lives there, a human being who’s special and unique. How is that achieved?

TK: I don’t think it’s rocket science. It’s like asking, Mark, why are your articles always so well written and so interesting and provocative? Because you are. You’re thinking about stuff, you’re thinking about what’s around you. A good architect does the same thing. You spend your waking hours thinking about how we move in space. What’s the flow of people, what’s the social distancing? What’s the cultural distancing?

I always say successful architects are successful voyeurs. You’re just looking and thinking. You’re looking out and watching everything that’s happening in front of you. An architect is always thinking, how is this thing working? It’s observational science. That’s why I think older architects can be better at designing places that feel right. You just have more experiences. You have more tools in your tool belt.

“I always say successful architects are successful voyeurs. You're just looking and thinking. You're looking out and watching everything that's happening in front of you.”

MR: Do you feel that with yourself as your career moves along?

TK: For sure. Sometimes I work with clients that are really sophisticated and have done other projects, and we share an almost nonverbal understanding of the end game. But sometimes a client is less experienced, and they depend even more on that tool belt you bring. It’s another kind of voyeuristic situation – you’re watching how a client works.

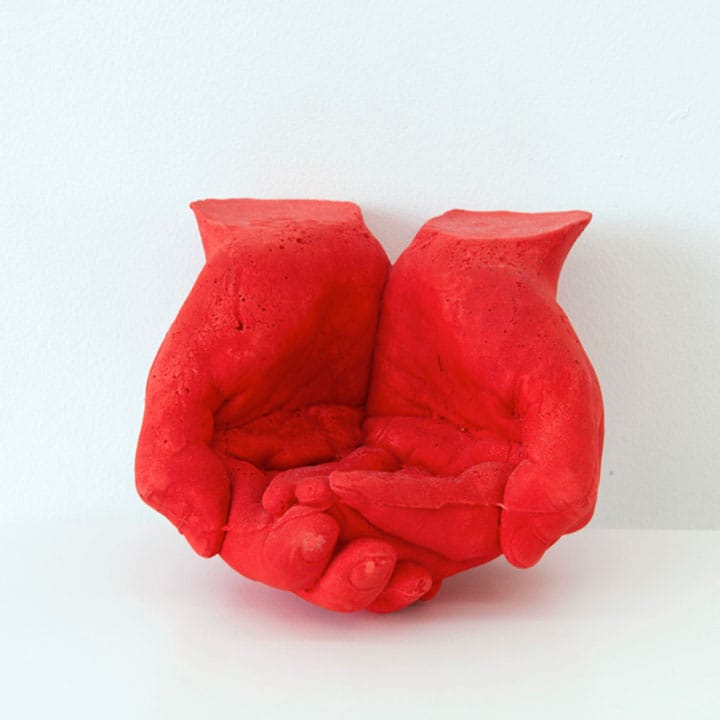

It’s like somebody who collects art. I appreciate art at a certain level, but a true curator takes it to the next level. When they teach you, they’re sort of taking you by the hand to show you something new, and then you appreciate the art so much more. You didn’t get there alone because you hadn’t seen enough art, you hadn’t studied enough to recognize all of the nuance.

MR: That’s interesting to me because it gets to the back and forth between an architect and a client, which I assume has to be handled in such an open and tactful way.

TK: Ultimately a house is a dialogue between a client and an architect. The building is the physical manifestation of that conversation.

MR: I don’t think I’ve ever thought of architecture in quite that way. It has to be collaborative, open to suggestion.

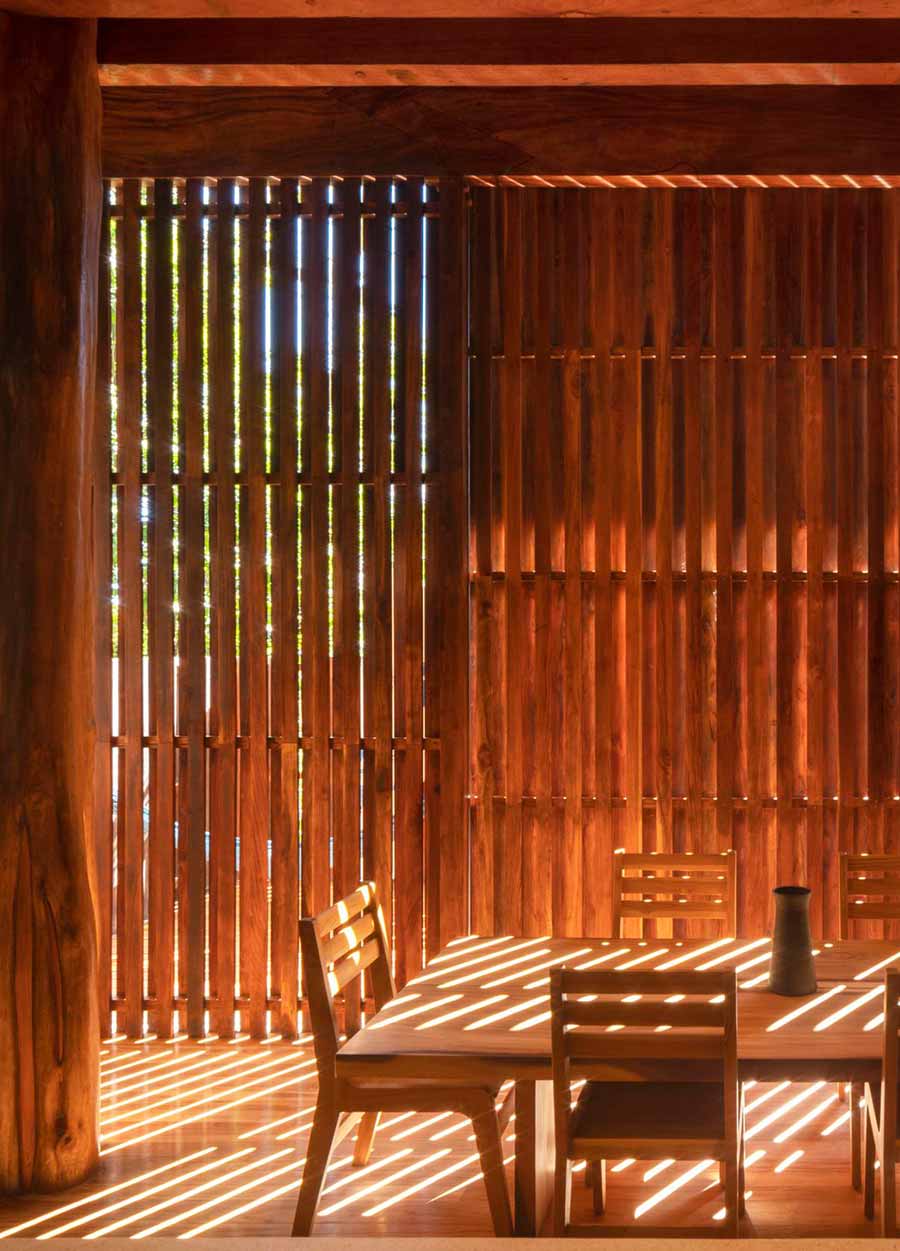

TK: Exactly. That’s one reason I like working on buildings at a variety of different scales. The smaller scale projects are those little jazz moments – you can experiment, you can play. You’re getting close to the fire, the meaning of being human. Everything is contextually based – it’s the client, it’s the landscape, it’s the program, the budget, the materials. It’s the tectonics. It’s an exploration.

“Ultimately a house is a dialogue between a client and an architect. The building is the physical manifestation of that conversation.”

MR: But at the other end of the spectrum are larger institutional projects – like the Burke Museum in Seattle, which opened last fall. There’s nothing small about that project. How do you bring those same touches and detail and intimacy to something that scale?

TK: The question is a good one, and especially important to me because no matter the scale of the building, the people occupying it are the same. You’re appealing to the same sense of being a human being, with all our fragility and intelligence, our need for social interaction. If you’re skilled at understanding what a given space is all about and how you flow through it, what’s a comfortable proportion, then you can scale it up for a larger community.

MR: One of my favorite phrases that you like to use is “Tootsie Pop” – being hard on the outside, soft on the inside. It gets right to the heart of the matter, the dichotomies that run through your work and make it so dynamic. When we spoke at the Glass House last fall, you spoke about ecotones as an exciting place for design. You defined it for me as a place in the landscape or the environment where two different kinds of terrain or ecosystems meet or overlap in an interesting way.

TK: I’ve been thinking about this more and more since that conversation, and it dawned on me recently that an ecotone is that yin and yang experience. I used to use “ecotone” to mean the spot between the meadow and the forest – you want to put a structure there, because you’re protected but still you can look out across the landscape and see what’s coming. It’s a defensive position. But there’s an ecotone in virtually everything we do. Architecture is about how we navigate those thresholds. That’s where the magic begins to happen and that’s where things change.

MR: We’ve talked a bit about “ugly” buildings in the past, and it’s something you seem to be exploring, in terms of repurposing buildings that might be looked at a little unfairly, viewed as an eyesore.

TK: In retrospect, I’ve been thinking about this for a long time. Even in my own house – known as Hot Rod House – I gave Jeannie, my wife, specific direction to find a really awful building in a good spot. I didn’t want to feel like I was taking an important, special building and re-assembling it. I want to get a somewhat discardable building, something no one would give a second thought to, and try to make something out of it.

It isn’t necessarily less expensive or faster to work from an existing building; in fact, it can be the opposite. But what it does do is pull along some of the built history of the site into the new building, and I think that makes for a richer building. You sort of repurpose “ugly” into your own language and start a new conversation. I think it’s the architecture of the future.

I’m just finishing a building in West Hollywood – 8899 Beverly – that revised an office building into high-end condominiums. There was enough structure and integrity within the existing building, that there was no reason to take it down. There were so many reasons to leave it in place. There’s the embodied energy, of course, but also the soul and the history. Oddly, it’s been like continuing a conversation with architect (Richard Dorman) that’s long since passed away. This building is the physical remnant of an earlier conversation, many years ago, back in the early 1960s. And I’m hoping in another forty, fifty years, another architect comes along and sees something again in that building and picks up the conversation.

It’s totally fascinating to me that rather than an intact, self-contained narrative, the story of this building transitions to a new narrative. It’s that threshold again, the ecotone between the historic and the new.

“You sort of repurpose 'ugly' into your own language and start a new conversation. I think it’s the architecture of the future.”

MR: It creates a very rich fabric in terms of design, and I imagine it also presents interesting opportunities and limitations to bump up against, triggering creativity.

TK: Exactly. Especially with an older building, the obstructions or challenges or unknowns you come up against lead to more interesting solutions, ultimately.

MR: Speaking of unknowns – we’ve known each other for 15 years, and we’ve hung out across the world, from New York to London to Seattle. Now here we are in the middle of nowhere in the space of Zoom in 2020. Who would have imagined?

TK: You know, so many people have contacted me to say they loved reading your introduction in my new book. One of the benefits of what we’re all kind of collectively experiencing is that people have time to really read things, to dig into books. I’ve never had the kind of response to the narratives in any of my books that I’ve had with this one. We lead busy lives; previously, people would flip through and look at photographs, and that’s what they had time to do. But now people are really reading things and getting into them and sending me responses. There’s been a terrific response.

MR: People are getting more meditative, maybe.

TK: I hope so. I’m sick of the words “silver lining,” but that might be one of the most important silver livings in all of this: being more thoughtful about next steps.

MR: Do you see anything that might be lasting, in terms of the impact of this on your designs?

TK: I think it’s an evolution, not a revolution. There will be some impact – I don’t know exactly what yet. Right now, we’re in a bit of chaos and turmoil, but after it settles, I’m hoping we get something out of it. I hope I don’t travel as much. I hope people are more thoughtful about what they’re doing with their home life, travel life, business life, family life. More thoughtful about the environment. More thoughtful about how we treat each other. That may be Pollyanna kind of thinking, but I hope some good will come out of this. How much, I’m not sure – but something.

Share This Page